1824 – 200th Anniversary of the Ionian Academy

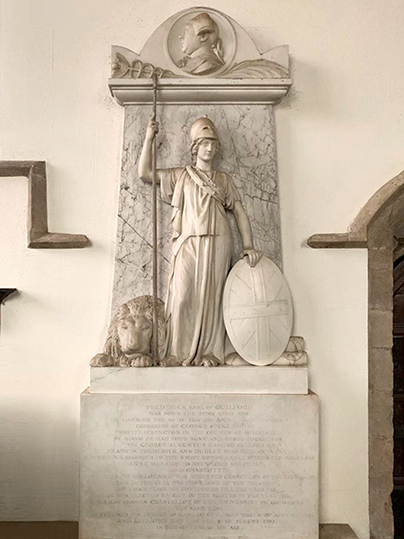

Tribute to Frederick North, Earl of Guilford

Edited by Megakles Rogakos, MA MA PhD

[FOR GREEK TEXT SEE BELOW]

Of gratitude to Guilford and a wish for the future of the Ionian University

Arguably, Guilford was the greatest philhellene of all time. He was obsessed with Hellas and aimed to found the Ionian Academy in Ithaca, the birthplace of his idol, Odysseus.

More importantly, however, he reminded the academic world of the Hellenicity of its origins, ideals and language. The greatest legacy of Guilford, however, was to reinstate a generous understanding of what it is to be a Hellene.

He was a dedicated follower of the famed dictum in Isocrates’ Panegyricus, “the name Hellenes suggests no longer a race but an intelligence, and the title Hellenes is applied rather to those who share our culture than to those who share a common blood” [Isocrates, Panegyricus 4.50]. So, by embracing the Ionian islands and caring for education there, Guilford was being true to his own calling as a man who could rightfully claim the title of Hellene.

What is more, showcasing the work of Guilford is one of the finest means to build cultural bridges between Greece and England. That is why the 200th anniversary of the Ionian Academy is a golden opportunity to celebrate Anglo-Hellenic relations. This has been the main mission of both Lord Jacob Rothschild (1936-2024) and Count Spiro Flamburiari (1930-2023), both of them Hellenes in the broadest and loftiest sense. These two most honourable late gentlemen are the closest cultural heirs of Guilford, and – following their recent passing – are both already sorely missed. We are deeply grateful to them both for being outstanding examples of Hellenic virtue, as was Guilford himself.

Given this significant anniversary, one of the many ways in which we can honour Guilford is to send a message of hope and encouragement to the Ionian University. We would like to wish it longevity and success in charting its future as a competitive, extrovert and innovative place of learning that inspires young people and meets their ever-evolving needs. That is in keeping with Guilford’s Hellenic ideal and vision.

Megakles Rogakos, MA MA PhD

Art Historian and Editor-in-Chief of the present volume

§

Frederick North, the 5th Earl of Guilford

It is always a great pleasure for any British Ambassador to Greece to find an occasion to be associated with an event, a personality or a place linked to the island of Corfu.

Corfu enjoys many strong historical and cultural connections with the wider Greek-British relationship and is of course also associated with carefree days of relaxation and enjoyment of life and of artistic and intellectual creativity for many of my compatriots, through the ages.

If one were to single out a particular figure who – because of his love of Corfu, his love of Greece and his immense contribution in laying one of the biggest foundation stones of our relationship – came to embody the British connection with Corfu, then surely, Frederick North, the 5th Earl of Guilford, would be the obvious choice.

Son of the Second Earl of Guilford who, as Lord North, was Prime Minister at the time of King George III, Guilford started his acquaintance with Greece from Corfu, in 1791.

From there, he travelled extensively in Greece and his interest and affection for all things Greek were demonstrated by his secret conversion to the Orthodox faith, when he was only 25 years old. This made Guilford the first and perhaps still one of the few Orthodox Christians ever to sit in the British Parliament.

I won’t go into the well-known details of Guilford’s distinguished career as Governor of the island of Ceylon (present day Sri Lanka) and his later appointment as Director of Education for the Ionian Islands. But, it was this last posting that, coupled with Guilford’s interest in the classics and letters more widely, led to his life’s great achievement, the founding of the Ionian Academy, the first university to be established on Greek soil, two hundred years ago, in 1824.

His past as member and later President of the Philomuse Society in Athens, his passionate interest in the ancient Greek world and, of course, his generosity (he bequeathed the Academy’s library 10,000 volumes from his personal collection) were the bases for the success of the undertaking.

To be sure, there were at those times, in the years before the outbreak of the Greek Revolution of 1821, a number of institutions of learning, one could say “colleges”, in the Ottoman Empire, on Chios, Kydonies, Smyrna and elsewhere. But the Ionian Academy was the first and only proper university in the Greek-speaking world, until the establishment of the University of Athens, in 1837. Guilford had every right to be proud of his creation and he even designed himself the costume he wore on the opening ceremony, a costume apparently combining both ancient Greek and contemporary elements.

When, today, we diplomats and our academic partners in Greece and the UK are talking about the paramount importance of education in the bilateral relationship, the successes of co-operation between Greek and UK Universities, scholarships, alumni networks and all the links that bind and strengthen us, we should always spare a moment to think about the dedicated idealist who started it all.

Closing this short note of gratitude, I will quote Professor Richard Clogg who wrote a paper on the subject in 2016 and refers to Frederick North, the 5th Earl of Guilford as “a man whose philhellenic sentiments and educational endeavours led to his making more of a contribution to the future development of Greece than many of the other philhellenes. He was an eccentric individual admittedly… but his attachment to everything Greek…[does], I think, merit calling him the philhellene’s philhellene.”

Matthew Lodge

HM Ambassador to Greece

§

Guilford, Founder of the Ionian Academy in 1824

It is good that his admirers on Corfu are paying tribute to the 5th Earl of Guilford, founder and ornament of the Ionian Academy, because although his contribution to the history of arts and letters in the Ionian Islands does not match that of the greater Ionian poets, he certainly did add to the pleasure and entertainment of many Corfiots and others, not just for his devotion to Greece and to the poetry of the ancient world, but for his unmistakable style of clothing including his headdresses and variety of hats. I suppose he takes his place as one of the most memorable eccentrics of his time. It is good that he is remembered to this day in the island, which he adorned not only by his dress but also with his books and his literary excursions. We remember him with a wry smile, but also with respect for what he achieved.

Sir Michael Llewellyn-Smith, KCVO CMG

British Ambassador to Greece (1996-1999)

§

Tribute to Guilford

Anglo-Hellenism has a long history and most of us, who occupy ourselves with the relations between Brits and Greeks, have our favourite characters in it. Mine come in different guises. They start with ecclesiastics, such as St Theodore of Tarsus, who arrived in Canterbury in 669AD as the first and so far only Greek head of the Church in England. Then, in the seventeenth century, we have Patriarch Cyril Loukaris of Alexandria and Archbishop Abbot of Canterbury, who agreed that Greek students could study theology in Oxford (education is a recurrent theme in Anglo-Hellenism). Later in the same century, Archbishop Georgirenes of Samos founded the first Greek church in London and set up a short-lived Greek College in Oxford. Across denominational lines, churchmen threw ropes to build bridges. They continue to do so. In our own time, the example of the late Bishop Kallistos Ware burns brightly.

The intellectuals are also central to this story. Capetanakis, Finlay, Gordon, Leake, Runciman, Stangos, Sherrard: there are many distinguished names to reckon with. And the creative writers too have played a hugely important part: Byron, Shelley and Kalvos in the nineteenth century; Durrell, Leigh Fermor, Valaoritis in the twentieth. In the revolutionary war, the bicentenary of which we continue to celebrate, the Philhellenes, of course, took to the field, as warriors, agitators, liberal idealists. Think of Church, Hastings, Byron (again), Stanhope, Trelawney. And for two centuries now, politicians in each country have taken inspiration from the other and driven our mutual interests: Canning, Mavrokordatos, Gladstone, Tricoupis père and Tricoupis fils, Venizelos, Lloyd George, Churchill. There have been significant diplomats too: Gennadius above all, but also, I think, Leeper, Seferiadis. Add to this gallery the leaders of Anglo-Hellenic businesses (those famous families whose most enterprising sons and daughters are illustriously buried at West Norwood in London), and, in our own time, artists and designers like Craxton, Issigonis, Kokosalaki, Takis.

Many great names, providing much food for thought. There is no single thread that joins them all, except for Anglo-Hellenism itself. But there is one notably vibrant strand: eccentricity. Anglo-Hellenism has often been an eccentric pursuit and some of its leading exponents could well be considered eccentrics. One man in particular stands out both for the depth of his Philhellenism and for the sheer ebullience of his eccentricity. He is Frederick North, the 5th Earl of Guilford (1766-1827). I am much indebted to a hetherto unpublished lecture about him given by Richard Clogg in 2016 at the Ionian University with the characteristic title “The Philhellene’s Philhellene”.

It was, indeed, as an eccentric that Guilford first came to my attention, many years ago. Here, I learned, was a man who, during the British Protectorate of the Ionian Islands, consumed a good part of his fortune to live on Corfu like a Platonic philosopher, dressed in what he took to be the robes of a 5th-century Athenian (on Guilford’s eccentric sense of dress, see Jonathan C. Cooper, ‘The Academical Dress of the Ionian Academy, 1824-1864’, Transactions of the Burgon Society, 14, 2014: 35-47). Contemporaries like the tough and dour High Commissioner, Tom Maitland, did not take him quite seriously. And yet, two hundred years later, we are now celebrating the anniversary of the Ionian Academy, which Guilford founded. Seriousness of purpose shines out through the eccentric reputation.

In some ways Guilford was hardly a Philhellene at all by contemporary standards: apart from some help raising funds, he kept out of the independence struggle and never saw military or humanitarian action in it. But he has, I think, a credible claim to being the most complete of all the Philhellenes of his age, perhaps even more so than Byron. Like many young men of his class and era, he had studied the Classics deeply and fell in love with Greece, ancient and modern, when extending his Grand Tour to the Ionian Islands and mainland Greece (1791-1792; he was in Greece again in 1810). Perhaps he acted impulsively, perhaps he arrived with a firm mission in mind; at any rate, on that first tour he was received by baptism into the Orthodox Church, and he appears to have kept the Orthodox faith to the end of his life (the evidence is reviewed in Kallistos Ware, “The 5th Earl of Guilford and his Secret Conversion to the Orthodox Church”, published for the Ecclesiastical History Society by Basil Blackwell, Oxford 1976. He also set about learning modern Greek proficiently. After serving as Governor of Ceylon (1798-1805) and inheriting the family title and wealth (in 1817), Guilford returned to the Ionian Islands, now under the British Protectorate, and conceived his great project: to found a university for Greeks.

This too may have seemed like an eccentric or even quixotic enterprise. But as recent scholars have shown, Guilford undertook it with thorough professionalism and administrative skill (see, e.g., George-Patrick Henderson, The Ionian Academy, Edinburgh, UK: Scottish Academic Press, 1988, especially chapters 2-5; Helen Angelomatis-Tsougarakis, The Ionian Academy: The Chronicle of the Founding of the First Greek University – 1811-1824, Athens, GR: Mikros Romios, 1997, especially chapters 14-16; Eric Glasgow, “Lord Guilford and the Ionian Academy”, Library History 18.2, July 2002: 140-143). He wanted to create a seat of genuinely up-to-date European learning, drawing on the best European models; and he knew that a condition of its success was the creation too of a suitable system of pre-university education on the islands. He wanted teaching in his university to be, as far as possible, in Greek. Like his contemporary Byron, Guilford was wealthy and he invested his own fortune heavily in the project.

Had he lived longer, the Ionian Academy may well have had more than local significance. Posterity, however, was not so kind. In 1864, the Hellenic Kingdom – with its centralising tendencies and weak finances – decided it could not afford universities both in Athens and on Corfu. Thus the Ionian Academy ended then. But it is testimony to the persistent Greek love of learning and to the spark that Guilford kindled that the Ionian University should be refounded on Corfu in 1984.

Few can doubt that higher education is one of the strengths of today’s British-Greek relationship, with many Greeks studying and working in British universities, and many Brits, like Guilford over two hundred years ago, studying Greece across the ages. I hope that the bicentenary of Guilford’s original foundation will offer further possibility for reflecting on and strengthening Anglo-Hellenic educational interests. And I salute this initiative by the Corfu Heritage Foundation.

John Kittmer, PhD

Chair, Council of The Anglo-Hellenic League

British Ambassador to Greece (2013-2016)

§

Lord Guilford

Two centuries ago, the academic landscape of Greece was transformed by the creation of the Ionian Academy by Lord Guilford, born in 1766 to an illustrious lineage. Guilford’s life was shaped by rigorous education at Eton and Christ Church, Oxford. His travels through Greece inspired him and developed his profound affinity for Greek culture.

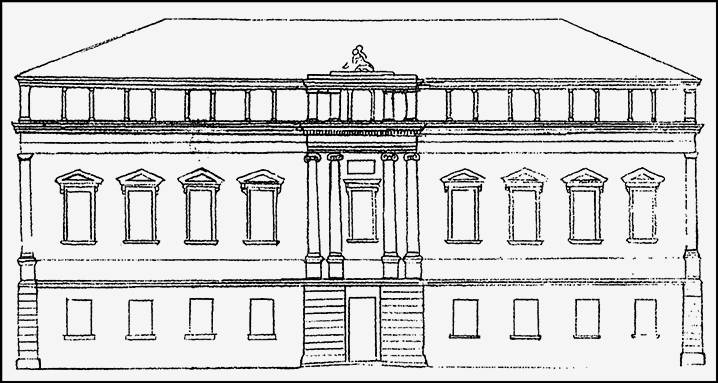

As the winds of change swept through Europe after the Congress of Vienna in 1815, with the British protectorate securing the Ionian islands, Lord Guilford’s vision of the Academy brought about a beacon of higher education, steeped in Greek intellectual traditions, yet forward-thinking in its approach. Initial plans to house the Academy in Ithaca gave way to Corfu, setting the stage for the establishment of this institution in 1824.

At the heart of the Academy’s curriculum stood the ancient Greek language and its culture, but in addition embraced the subjects of English literature, mathematics and botany, which representing a confluence of Greek heritage and modern thought. Drawing luminaries of the Greek academic world to its faculty, the Academy attracted no less than 150 students in its maiden year.

As we commemorate the 200th anniversary of the Academy, we celebrate not only an institution, but a legacy – one which married the classical with the contemporary world. Lord Guilford’s dream not only enriched the academic tapestry of the 19th century but continues to inspire us today.

On a personal note, I am particularly proud that Lord Guilford and I have a certain amount in common: we were both educated in the same colleges of Oxford. We have both received honorary degrees from Oxford University and have been members of the Society of Dilettanti, who share their passion for Greece and Rome. A hugely important factor in our lives has been our great love, for the beautiful island of Corfu. Lord Guilford’s unique contribution to academic life on the island will be cherished and shall be remembered forever.

Lord Jacob Rothschild

Chairman of the Rothschild Foundation

§

Ionian Academy

With the present album, we honour the 200th anniversary of the Ionian Academy, founded by Lord Frederick North, 5th Earl of Guilford, in 1824.

Now known as the Ionian University, this Academy was the first Greek-speaking academic institution of modern times. Guilford envisaged a Greek academy’s creation; which he was determinably to achieve in the Ionian Islands, a place that is as hard and rugged as it is soft and wonderful. This noble Englishman’s embrace of Hellenism, together with its religious Orthodoxy, enabled all his great achievements. And, thus, it was that there was established by him, in manifest and tangible form, the first great cultural bridge between Greece and the United Kingdom.

Guilford had also created a very extensive library comprising rare books and manuscripts that was considered outstanding, even during his own lifetime. His intention and stated wish was to house it in ‘his’ Ionian Academy, set within the soul of Ithaca, the homeland of Odysseus. Howsoever that it transpired that Guilford’s relatives dishonoured that dying wish as stated in his will. But fate was on his side, despite his heirs’ moral turpitude in dealing with his effects, in that these most precious books and manuscripts are preserved in the British Library. For fate decides certain things despite man’s follies. For indeed, had his library remained in its building in the Old Town of Corfu, it would have had suffered the same destruction by fire of Prosalenti’s legendary bust of Guilford, which, together with the building in which was housed, was completely destroyed by the German Luftwaffe’s incendiary terrorist bombing of Corfu, during that horrific night of its own “Guernica”, on the 13th of September 1943.

I am delighted that the Earl of Guilford’s portrait as well as the Degree awarded to him by the University of Oxford in 1819 – both together now adorn the entrance hall of the Ionian University’s Rectory. May this achievement, due to the collaboration of the Rothschild Foundation and the Corfu Heritage Foundation, in 2022, be an example to others and to us all.

This album shows us the necessary timelessness of educational values, which the Ionian University still holds high. Everyone contributing to this anniversary publication is a philhellene. In the past, philhellenes, like Guilford, were visionary protagonists who endeavoured to bring attention to Hellenic culture and to enable its dissemination. Today philhellenism is manifest throughout all the sciences – such archaeology, sociology, history, geometry and mathematics.

The Ionian University is ideally suited to serve its cause. We are most appreciative of all those noteworthy philhellenes of the past – and, now, those who continue in our own times – such as they who have contributed their essays in this noble academic memorialising context.

The 200-year history of the Ionian Academy is rich with advances and, alas, setbacks – such as war and the privations it brings in its malign wake. Yet, may this anniversary mark an ascending and advancing curve for the Ionian University – that all such may be for the benefit of its students, for those that are to follow and so onwards for the benefit of society as a whole, present and future.

Count Spiro Flamburiari

Chairman of the Corfu Heritage Foundation

§

Lord Guilford, the forgotten philhellene: How an eccentric British aristocrat founded the first university in modern Greece

By Alex Sakalis, MA

The distinguished writer on Greek affairs, C.M. Woodhouse, once wrote that the two most influential Hellenophiles in Europe were Lords Byron and Guilford. But while Byron, whose life exemplified the golden age of the romantic idealist and roving revolutionary, remains idolised in both Britain and Greece, Guilford has faded into obscurity. Yet Lord Guilford, the eccentric aristocrat who founded modern Greece’s first university, remains one of the most fascinating and elusive figures of the golden age, unlike anyone else of that era, a rogue among rogues.

Guilford was born Frederick North in 1766, the youngest of three sons of Lord North, who was Prime Minister between 1770 and 1782, during which time he notoriously ‘lost’ the American colonies. Like his father, the young Guilford attended Eton and Oxford after which he travelled aimlessly and took sinecure posts in Ceylon and Corsica. All this was meant to groom him for a political career like his father.

Instead, while on a visit to Greece, Guilford fell madly in love with the country, mastering the language and converting to Greek Orthodox Christianity, much to the displeasure of his family. He spent the rest of his life working for the cause of Greek emancipation through education, establishing in Corfu the first university in modern Greece, providing scholarships for Greek students to study abroad, and embellishing the university with thousands of valuable books from his personal library. During this time, he rubbed shoulders with iconic figures such as Lord Byron, Ali Pasha and Ioannis Kapodistrias, independent Greece’s first President. Largely disowned by his family back in England, he continued to devote his entire life and finances to helping the Greek people until his death, unmarried and childless in 1827.

Guilford first visited Greece in 1791, arriving in Corfu and spending the next two years travelling the country, most of which was under Ottoman rule at the time. He quickly fell in love with Greece, mastering the language and absorbing the history. In 1792, Guilford returned to Corfu where, at the age of 25, he converted to Greek Orthodox Christianity, causing him to be shunned by his family. Incidentally, he became the first Greek Orthodox Christian to sit in the British Parliament – he was MP for Banbury at the time – and perhaps the only one until the election of Bambos Charalambous as MP for Enfield Southgate in 2017. For political reasons the conversion was kept secret from everyone except his family and close friends – this was at a time when Catholics were banned from sitting in Parliament and having to deal with a Greek Orthodox MP would have been too much of a headache for the political establishment.

Although Guilford continued to travel extensively, including a stint as governor of Ceylon, his heart remained in Greece. In 1814, he became president of the Society of the Friends of the Muses in Athens, an organisation that brought together philhellenes and members of the Greek intelligentsia. His time in Athens, still under Ottoman rule, consolidated his desire to do something for the cause of Greek emancipation.

In 1815, he attended the Congress of Vienna where he met Ioannis Kapodistrias, the future President of Greece. They discussed founding an institute of higher education in the Ionian Islands, which had just become a British Protectorate. They reasoned that an autonomous, self-governing Greek university, with Greek professors and Greek students, would be an important step in the emancipation of the Greek people. Guilford was enraptured – he had finally found his calling.

By this time, he had inherited the title of Lord Guilford from his father and began to exploit all his connections to realise his mad project of building a university on Corfu. He convinced Lord Bathurst, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, to appoint him director of education for the Ionian Islands. In 1824, the Ionian Academy opened its doors. Its professors numbered some of the finest Greek minds of the day, teaching subjects as diverse as mathematics, botany and English.

Perhaps in protest of Britain, where Catholics were forbidden from attending Oxford or Cambridge, Guilford made sure the Academy was open to any man of any faith. However, as in Britain, only men were eligible for admission. There was also a strict code of conduct that banned everything from drunkenness to “conduct unworthy of a gentleman”. Rulebreakers were confined to the island’s fort for up to a month. This was to be a place for serious academic study only.

Guilford nearly bankrupted himself by buying rare books to fill the Academy’s library, which had already been embellished with his own collection. At its peak, the library had 30,000 tomes, including “the most complete collection of modern Greek literature in the world”. He paid scholarships for promising Greek students to study abroad, with the expectation that they would return to teach at the Academy. He also financially supported many Greek students from the mainland who could not afford living expenses in Corfu.

Guilford died in 1827, unmarried and childless, having devoted his entire adult life to the cause of Greek emancipation through education. Unfortunately, this would be the beginning of the end for the Ionian Academy. His relatives in Britain fought over his will and managed to reclaim many of his books, decimating the library. Without Guilford’s patronage, the Academy struggled for funding and lost many of its most talented staff. After the union of the Ionian Islands with the Kingdom of Greece in 1864, the Ionian Academy was closed to support the newly established University of Athens. Corfu would be without an institute of higher education until 1984, when the Ionian University was created as the successor to the Academy.

Guilford was certainly eccentric. He dressed in ancient Greek robes like Plato and conversed in an archaic form of Greek with the locals in Corfu. He also insisted on a strict dress code for students at his university, which was based on ancient Greek robes, with different colours for the different tiers of students. On the other hand, he recognised the importance of education to Greek emancipation and was conscious of the need to establish strong, self-governing institutions in Greece in preparation for the country’s eventual independence.

Contemporaries undoubtedly saw the importance of Guilford to the Greek national revival and state-building process, as can be seen by the naming of prominent streets in Corfu and Athens after him. A statue of Guilford stands in a garden not far from today’s Ionian University. Despite this, Guilford has largely been forgotten in both Greece and Britain. Byron, the swashbuckling hero, womaniser and poet whose untimely death during the Siege of Missolonghi helped galvanise international support for the Greek War of Independence, fits easily into a narrative of romantic philhellenes giving their life for the noble cause of Greek emancipation.

By comparison, it is difficult to fit Guilford into this narrative. His eccentricity was ridiculed, rather than admired. He was not a self-publicist and his contributions were far less dramatic, though no less important. He had no great affairs, no military exploits, limited contact with key figures in Greece and abroad and largely confined his activities to the academic field. As a result, he was excluded from Greece’s post-independence meta-narrative and largely forgotten.

But as Greece celebrated 200 years of independence, there has been a reappraisal of Guilford, rescuing him from the margins of history and restoring his status as one of the most important philhellenes. The Ionian University has recently set up the Guilford Project to research and promote his legacy while plans are afoot to nominate him as Corfu’s “personality” in the centenary celebrations. Meanwhile, last year’s Corfu Literary Festival hosted an event celebrating Guilford and venerating him as a pioneer of Anglo-Hellenic friendship, a full century before the Durrells arrived. Of course, Guilford, being the modest man that he was, would find all this fuss over him a bit embarrassing. And yet it’s modest men like him who deserve to live long in the memory.

[Talk given at the Holy Trinity Anglican Church, 16 September 2021]

§

Frederick North (1766-1827), the 5th Earl of Guilford – The Philhellene’s Phillhellene

By Professor Richard Clogg

In 2021, the 200th anniversary of the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence has prompted the publication of numerous books and articles recording the feats of arms of the insurgents and those of the philhellenic volunteers who hastened to the Greek lands to offer their services in the struggle to overthrow Ottoman rule. It was not surprising that these publications have tended to focus largely on the military aspects of the war to establish an independent Greek state, an undertaking which in the eyes of many contemporary observers seemed unlikely to succeed.

In a book published to mark the 150th anniversary of the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence, Alexis Dimaras contributed a chapter devoted to what he termed ‘the other British philhellenes’, those who, while they did not take part in the fighting, nonetheless engaged in activities intended to advance the philhellenic cause. (“The Other British Philhellenes” in Richard Clogg, ed., The Struggle for Greek Independence, London 1973: 200-223). One the most important of these ‘other philhellenes’ was Frederick North (1766-1827), the 5th Earl of Guilford. When the war broke out Guilford was in his mid-fifties and was far from being a martial figure. Yet he was one of the most effective and committed of the philhellenes and was instrumental in the foundation in 1824 of the Ionian Academy in Corfu which was in effect the first university to be founded in the Greek world. William St Clair in his excellent study of the contribution of the philhellenes to the war of independence, That Greece might still be free. The Philhellenes in the War of Independence (London 1972) devoted only half a page to him in a book of 400 pages.

In 1817 he had become the 5th Earl of Guilford following the death of two older brothers. Helen Angelomatis-Tsougarakis has published a striking observation by Guilford when he argued “to be sure I am partial, but I consider the Greeks of the nineteenth century as far superior to those of the fifteenth, and within these twenty years the advances they have made in science, navigation, trade and independence of spirit are inconceivable. The idea entertained of them in the West is a very false and imperfect one and I do not believe that any other nation in the world could have done so much for itself under so long and severe a bondage.” (“The Travels of Lord Guilford in Greece” in Proceedings of the 5th International Panionian Conference, Argostoli 1990: ii 76 / published in Greek).

Guilford was that rare foreigner whose admiration for ancient Greece and its civilization was equalled by his interest in post-Byzantine Greece and its culture and, in particular, in his zeal for the promotion of the educational opportunities afforded to its people. Even rarer, in 1792 the twenty-six year old Guilford had become a secret convert to Orthodoxy. This was no passing enthusiasm on his part for on his deathbed thirty-five years later he called for Father Yakov Smirnov, the chaplain to the Russian Embassy in London and a diplomat, to administer the last rites. Guilford was very probably the only one of the British philhellenes to have adopted the religious beliefs of the Greeks for whom he had such a concern. Guilford died on 14 October 1827, at the age of sixty-one, six days before the battle of Navarino which saw the defeat of the Ottoman and Turco-Egyptian fleets by a combined British, French and Russian fleet. This, the last great naval battle in the age of sail, was to ensure that some measure of independence for Greece would come about. It would surely have pleased Guilford had he lived long enough to learn of this victory.

Guilford had visited the Ionian islands and the Ottoman Empire in 1791 and 1810-1813. He was to assume the role of honorary president of the PhilomuseSociety. This had been founded in 1813 in Athens with the objective of promoting education in the Greek world. Soon after its foundation it numbered 21 Athenians and 22 Britons among its members. Two years later in 1815, Guilford visited Vienna while the Congress of Vienna was engaged in reshaping the affairs of Europe following the turmoil of the Napoleonic wars. While in Vienna, Guilford met with Count Ioannis Capodistrias, a Corfiot and at the time joint foreign minister with Karl Nesselrode in the service of the Russian Emperor, Alexander I. Capodistrias, who headed the Vienna branch of the Philomouson Etaireia, discussed with Guilford the possibility of the British founding an institution of higher education in the Ionian Islands, now that the Treaty of Paris (1815) had confirmed the British protectorate there, with the title “United States of the Ionian Islands”.

On assuming the title of the 5th Earl, Guilford had inherited the funds necessary for the creation of the Ionian Academy, his greatest achievement. Guilford initially intended that the Ionian Academy should be established on the island of Ithaca, with its supposed Homeric associations. But General Sir Thomas Maitland who had been appointed the Lord High Commissioner of the Ionian Islands opposed the choice of Ithaca. It was, in his view, too close to the hostilities on the mainland between Greeks and Turks that had broken out in 1821. Although Guilford was initially disappointed by Maitland’s decision he came round to a more positive view of the town of Corfu as the home of the Ionian Academy. The law courts of the Ionian Islands, for instance, were established in the town, as was the hospital. This proved useful in the training of lawyers and doctors. There were concerns, however, that some of the students might succumb to the temptations of city life.

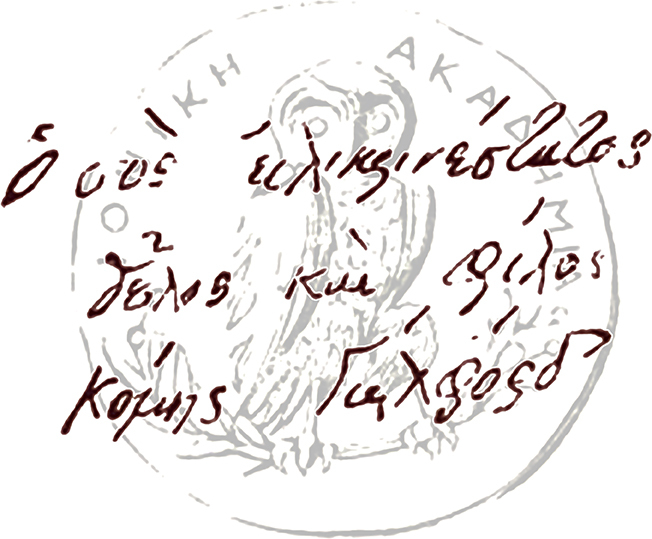

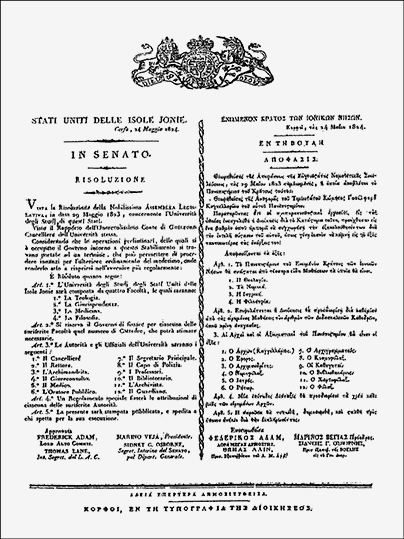

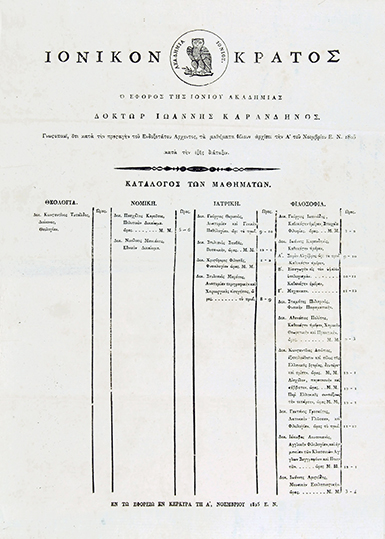

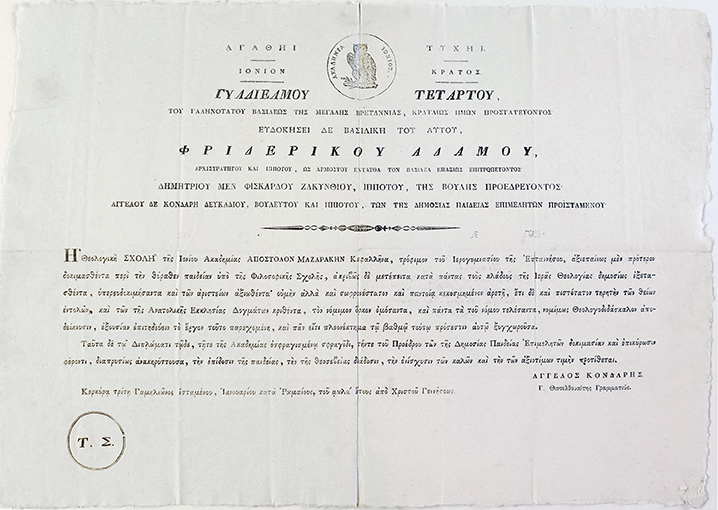

We are fortunate in having much information about the subjects that were to be taught at the Academy, which was in effect the first university to be established in the Greek world, and about their teachers. There were four faculties: Theology, Jurisprudence, Medicine and Philosophy. Guilford himself became the Chancellor (Arkhon) of the Academy as is indicated by his bookplate, which was changed from the coat of arms of the Guilford family to a marble slab with the inscription “0 ARCHON TIS IONIOU AKADIMIAS KOMIS GUILFORD” (The Chancellor of the Ionian Academy Earl of Guilford).

Seven professorships were established at the opening of the Ionian Academy. These were held by the cream of the Greek intelligentsia of its day. Taught in English, beside English language and literature, were history, rhetoric, mathematics, botany and philosophy. Guilford intended that, in time, vocational subjects, such as navigation and book-keeping, should be added to the curriculum. In the constitution of the Ionian Academy, it was stated that “any person of whatever country or religion he may be” would be eligible to enrol in the Academy but women could not do so (G.P. Henderson, The Ionian Academy, Edinburgh 1988).

One of the most impressive features of the Ionian Academy was the magnificent library that Guilford, ably assisted by the librarian he appointed, Andreas Papadopoulos Vretos, created. Guilford always intended that the library should remain in Corfu but this did not happen. A section of this superb library, which is of particular interest to the historian of modern Greece, consists of books published in Greek for a Greek readership in the critical decades before the outbreak of the Greek war of independence in 1821. What is essentially a catalogue of these was published by Papadopoulos Vretos in Athens in 1845 as a Katalogos ton apo tis ptoseos tis Konstantinoupoleos mekhri tou 1821 typothenton vivlion par’Ellinon eis tin omiloumenin i eis tin arkhaian ellinikin glossan (Catalogue of books printed between the fall of Constantinople and 1821 in spoken Greek or into ancient Greek). Such was Guilford’s consuming love for books that he is recorded as having said to Papadopoulos Vretos: “If I were not the Earl of Guilford I should have liked to be a librarian.” Guilford was not merely a bibliophile but a bibliomane, a person with a passionate enthusiasm for collecting and possessing books.

The great hall of the library of the Ionian Academy was modelled on the libraries of the University of Oxford where Guilford had studied at Christ Church. The opening hours of the library were generous indeed. Books would be fetched daily between the hours of 8 and 12 in the morning, 1-5 in the afternoon and 6 and 10 in the evening. The Corfu library was to be open daily, save on Sunday and religious festivals. Gifts to the library were recorded from the University of Cambridge, many of them relating to the study of classical Greece, the Marquis and Marchioness of Bute and the King of Denmark.

Guilford always intended that this collection should form the core of the library of the Ionian Academy, but that was not to be. Controversy surrounded his will, executed some three weeks before his death in 1827 and amended by a codicil added on 13 October, one day before he died. The will and codicil made the bequest of his books conditional on the Ionian government endowing the university with an annual amount of £3,500, a large sum in its day. It is difficult to avoid suspicions about these last-minute changes to his will that may well have been made at the behest of relatives anxious to secure a greater share of his estate for themselves. Guilford’s heir, Francis North, successfully argued that, in view of this stipulation not being fulfilled by the Ionian government, the executors of the will arranged for the return of much of Guilford’s library to England where it was eventually put up for sale.

The collection of pre-1821 Greek printed books amassed by Papadopoulos Vretos was sold in 1835 in London. This was listed in the sale catalogue as “Bibliotheca Graeco-Neoterica. A very Curious, Valuable and Extensive Collection of Books in the Modern Greek language”. It was described as “The most Extensive Assemblage of Modern Greek Books ever submitted to Public Sale. They were collected by the late Earl of Guilford for the Information of the Professors of the Ionian University, and the Instruction of the Greek Youths of that Establishment. No one possessed more opportunities of forming the best Collection of Modern Greek Books, and no one ever availed himself of his opportunities with more zeal, ardour or liberality than the late Earl of Guilford. The Collection consists of General Theology, Religious Offices, Homilies, Martyrologies, Ecclesiastical Histories, Treatises on Logic, Philosophy, Metaphysics, Geometry, Mathematics, Grammars, Poems, Histories, Translations of Ancient and Modern Authors… and Works in every Department of Literature. The Revival of Greece as an Independent State and its present active and increasing Commerce will necessarily lead to the study of its Language, and this collection will form a most useful, and perhaps for some years, a Matchless Library of Reference”. The entire collection of 627 volumes was bought for what was then the Library of the British Museum, which subsequently became the British Library, for the sum of 137 pounds and eleven shillings, a very modest sum for a collection that surely constitutes one of the greatest collections of pre-1821 Greek printed books anywhere, not excluding Greece. Joannes Gennadius, who was for many years the Greek Minister, effectively Ambassador, in London, a bibliomane like Guilford and whose own enormous personal library constituted the main part of the Gennadius Library of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens, described the removal of the collection to the library of the British Museum as an incalculable loss for Greece.

A large part of the very large number of manuscripts, some of them in Greek, from Guilford’s collection was also acquired by the British Museum. It was only in 2000 that the thousands of manuscripts from Guilford’s collection began to be properly catalogued in what is known as the ‘Guilford Project’. The motive of Guilford’s relatives in selling his books, manuscripts and even the academic dress that he had commissioned for the opening of the Ionian Academy was greed. This was revealed in an anecdote told to Papadopoulos Vretos by Georgios Papanikolas, one of the Greeks brought to England by Guilford at his expense for further study, in his case, of seamanship. Papanikolas approached Guilford’s cousin and heir to the Guilford title, who was also a clergyman in the Church of England, the Reverend Francis North, for money to pay for his return to Corfu. North is said to have replied: “If my cousin [Guilford] was mad enough to spend his money on you Greeks, I am not such a one, depart in peace, since you Greeks have consumed enough of the money of Count Frederick Guilford.” (Andreas Papadopoulos-Vretos, Notizie biografiche-storiche su Frederico Conte di Guilford, pari d’Inghilterra, e sulla da lui fondata Universita Ionia. Con note critiche-storiche su vari personaggi …Viographika-istorika ypomnimata peri tou Komitos Frederikhou Guilford omotimou tis Anglias kai peri tis par’aftou systitheisis Akadimias, Athens 1846, p.184 of the Greek text. Papadopoulos Vretos discussed the dispersal and the controverted provisions in Guilford’s will on pp. 152-183).

It would seem that the Reverend North’s meanness towards the young Papanikolas contributed to the latter’s jaundiced view of the benefits of British administration of the Ionian Islands. When George Bowen published a laudatory account of British rule in the islands entitled The Ionian Islands under British Protection (London 1851), Papanikolas, writing under the pseudonym ‘An Ionian’, published a vigorous riposte against Bowen entitled The Ionian Islands: what they have lost and suffered under the thirty-five years administration of the Lord High Commissioners sent to govern them (London 1851). Papanikolas had clearly acquired an excellent knowledge of English during his years in England and put this to good effect in his polemic directed against Bowen. He castigated the hapless Bowen as a man “whose appointment, whose salary, and whose perquisites are a scandal among the Ionians… An unripe scholar … [he] stands forth in his own person the theme of a hundred satires, and the laughing stock of English as well as Ionian Society in Corfu.”

In 2008 Vasiliki Bobou-Stamati published a detailed study of the almost 8,000 books that were collected for the Ionian Academy but were shipped back to London on his death. She rightly dedicated her study to the memory of Guilford “the most lovable and sincere of all the philhellenes, though never a combatant” (Vasiliki Bobou-Stamati, I Vivliothiki tou Lordou Guilford stin Kerkyra – 1824-1830 [The Library of Lord Guilford in Corfu – 1824-1830], Athens 2008: 16).

London, 1 December 2023

§

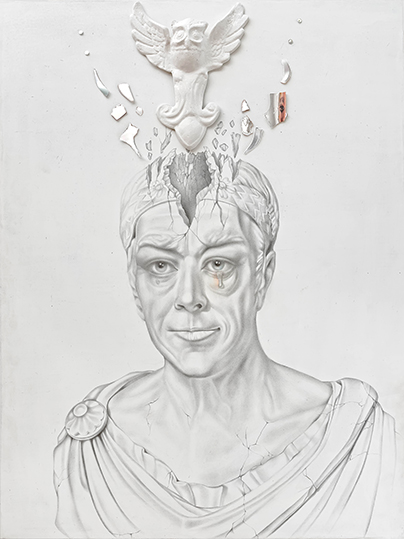

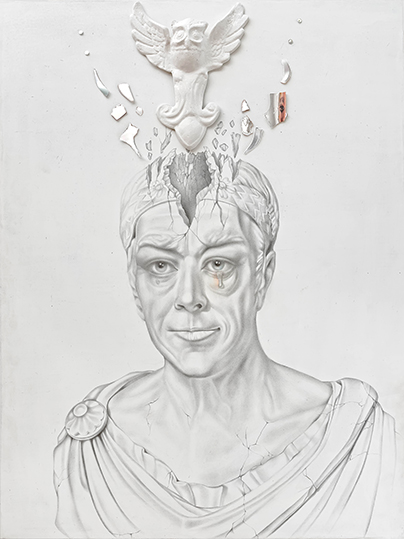

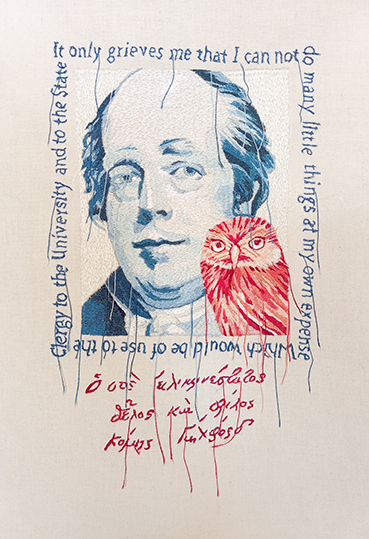

An attempted modern-era envisionment of the 5th Lord Guilford

The sublimest achievements, achieved against monstrous odds

By Robert Christoforides – author of The Life and Times of Wilfred Owen – A Biographical Novel

The monstrous odds, with which this extraordinary man, Frederick North, the 5th Earl of Guilford, sometimes known as Lord Guilford (referred to in this essay as ‘our Guilford’), had to contend, were both of inner familial malignities as well as having to struggle against staggering external obstacles and prejudices. A picture, such as the present case, is worth a thousand words…

But perhaps it would be best to begin with this great man’s final achievement, in physical form, on the soil of the nation which now is Greece. Once that final achievement is considered, it is then that this great man’s background – and his trials and tribulations – will be seen as enablers of his achievements.

Ithaca was the home of our Guilford’s hero, Odysseus. In Homeric speech, Odysseus tells us of his birthplace (here, adapted from Richmond Lattimore’s translation).

I am Odysseus son of Laertes, who’s known before all men

for the study of crafty designs, and my fame goes up to the heavens.

I am at home in sunny Ithaka. There, there is a mountain,

leaf-trembling Neritos, which stands tall and, near, other islands float

around it, lying very close to one another.

There is Doulichion and Same, wooded Zakynthos,

But my island lies low and saturnine, last of all on the water, as it leans toward the dark,

The others facing east and sunshine. Mine’s a rugged place,

but a good nurse of men; and, for my part,

I cannot think of any sweeter place on earth.

(Homer’s Odyssey, ix.19-28)

The map below shows Ithaca – as it is in relation to the other Ionian Islands and the modern coasts of Greece. Note that Same is located on the Ionian Island now known as Kefalonia.

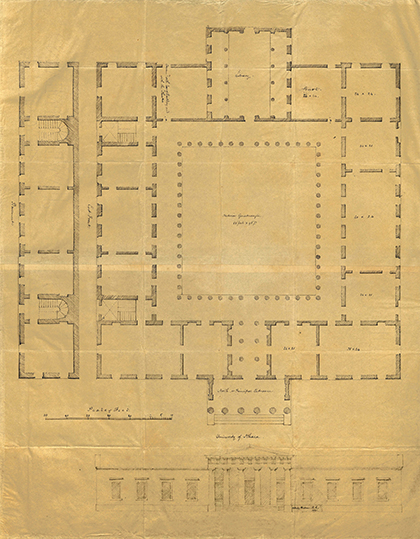

In July 1821, the engineer John Hulme designed the architectural plan for our Guilford’s intended building of the Ionian Academy on Ithaca. This was done in collaboration with our Guilford. It was based on a rough drawing by Charles Robert Cockerell RA (1788-1863). Here is a drawing of our Guilford’s dream, which implies Pythagorean proportionality.

But, alas, it was not to be. The War of Independence was raging in western Greece and Ithaca was a very unsettled place at that time. Our Guilford was thus conflicted. He was a fanatic supporter of Greece’s struggle; but it had terminally disastrous consequences for his plan for the establishment of his Ionian Academy on the island of Odysseus’ birthplace. So, he picked himself up from the gutters of despair and sited his Academy in Corfu – but, despite its huge success as a project, this, for him, was barely consolatory. But he accepted it stoically. And so, he died burdened with this tragic disappointment – at age 61 on 14th October 1827.

Often, it appears that history has little value. Certainly, it proves little. And most of its facts are either irretrievably lost or redacted by individual and collective omertàs. This is even more so the case in respect of individuals.

There is a plethora of facts about our Guilford. This essay attempts to explore how some facts in an individual’s life press upon that life, how their intervention shapes him consciously and unconsciously, how his inner world may be shaped by such and, finally, how such a conglomeration of events manifests itself in that individual’s life’s works. In this context, how are we to approach a historical understanding of Guilford, who was a British eccentric, politician, colonial administrator ‘who wanted to be Greek’?

His family began it climb of the ‘greasy pole’ of ennoblement when a Francis North was created 1st Baron Guilford (1637-1685). By today’s standards, the spelling of the name ‘Guilford’ is eccentric because any place with a name with such spelling appears not to exist in the whole of the United Kingdom – so the actual place of this name of ennoblement must be Guildford, which is a city south of London in the county of Surrey – in common English parlance the name of this city is spoken with the first ‘d’ being silent – so it is that, in fact today, this city’s name is spoken as our Guilford’s name is phonetically spelt. The meaning of the name, seems lost. Certainly, indicating a fording place across the river Wey – which is a tributary of the Thames – it may mean simply ‘people’s crossing’ or ‘toll crossing’ which would be a place where one can ford across the river, but only on payment of a toll.

Our Guilford was the fifth of six children – George Augustus North (1757-1802); Catherine Anne North (1760-1817), who married Sylvester Douglas, 1st Baron Glenbervie, and had no children; Francis North (1761-1817); Lady Charlotte North (died 25 October 1849), who married Lt. Col. The Hon. John Lindsay (1762-1826), son of the 5th Earl of Balcarres; Frederick North (1766-1827), our Guiford; Anne North-Holroyd (1782-1832). As is seen from the aforementioned list, he was preceded by two older sibling male heirs to the title and so, in his youth, would have had no reasonable expectation of inheriting the title – but, by chance’s strange arithmetic, he did so after the deaths, childless, of his brothers, George and Francis – hence he, becoming 5th Lord Guilford, was 51 years of age at the time.

He would have had a difficult childhood. His family was prominent and his father was Prime Minister when one of the most catastrophic events occurred in British history; that is, the humiliating loss of the American colonies. This was so catastrophic that it was suggested that his father should be impeached and the King even considered abdication. The national opprobrium against the family must have been considerable.

The war had become an international one for France and Spain – unwisely for them as it turned out – supported the colonies in their struggle. Their fleets were decisively defeated by the British admiral George Brydges Rodney (1718-1792) in the West Indies at the naval Battle of the Saintes. This transferred the strategic initiative to the British, whose dominance at sea was reasserted. News of the defeat reached the colonists, who realised they were no longer to have French and Spanish support in the future. During this war’s final crisis, Spain had put Gibraltar under siege with the intention of seizing it. Admiral Rodney’s victory enabled it to be relieved and so Gibraltar was retained by Britain.

No longer humbled, the British stiffened their resolve. They refuted claims by the colonists to the Newfoundland fisheries and to Canada. Not only did they drop their minimum demands and insist on the single precondition of recognition of their independence, they also put forward America’s abandonment of its commitment to make no separate peace treaty without the French. The victory at the Saintes brought about the collapse in the Franco-American alliance. Although Admiral Rodney’s victory might well have prevented a revolution in the United Kingdom, it could not reverse the American colonists’ inevitable march to independence, nor could it restore Lord North’s reputation – he had resigned in early 1782 – and his name, even today, is associated with, and a byword for, monumental and catastrophic failure.

Our Guilford would have been about 16 years old when the American War of Independence was coming to an end. The atmosphere at home must have been dreadful for him and his siblings. This unhappy atmosphere would have been of very long duration indeed, for the war was a long one – its official dates being 19 April 1775 – 3 September 1783. So, from the age of 8 to the age of 16, our Guilford, as boy and adolescent would have suffered greatly – and in the war’s aftermath, no less. He would have felt his father’s and family’s disgrace keenly. In these circumstances, the sensitive child turns inward. He creates his own world which takes him away from external sorrows and the contentions over which he has no control. None of Lord North’s children had children. This irregularity may have had the long shadow of the family’s enduring disgrace as its significant cause.

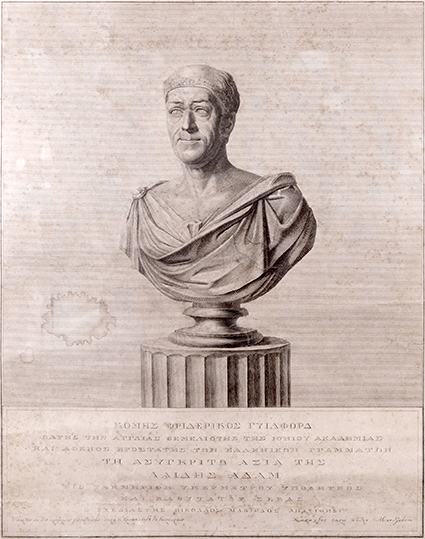

Now we can turn to the image – the face of this man. Pietro Mancion’s engraved portrait of our Guilford is said to be of or after the bust that Sir Pavlos Prosalentis (1784-1837) sculpted posthumously in 1827. This bust was destroyed by German fire-bombing of Corfu in 1943 and there is no photograph of it. None of the surviving pictures and sculptures of our Guilford has the inner characterisation which is disclosed in the printed image. In this face, we surely see one who saw himself as…

“A man despised and rejected of men, a man of sorrows and acquainted with grief…” [Isaiah 53:3-8 New King James Version Bible]

It is thus that “the sins of the parents are subtly visited upon the children” (Exodus 20:5). If this informed supposition is correct, then it must be that this image was created by someone acquainted with our Guilford towards the end of his life. It would seem likely that sketches from life were made as would disclose the face of one with such sorrowful memories inwardly conferred.

This implies a man of escapist fantastical imaginations. Perhaps, this is why, subconsciously, our Guilford had the support of George IV (1762-1830), for that Regent and King was also an indulgent fantasist and very prone to escapism– hence, for example, his extraordinarily brilliant Brighton Pavilion and his succumbing, alas, to gluttony. So, if we consider our Guilford in the context of his – perhaps subconscious – escapism and fantasism, perhaps we find keys to his visions and genius.

In his childhood and early manhood, he would have had an in depth classical education which would have included the ancient poets, most particularly, in ancient Greek, the epic poetry of Homer. This would have given a sensitive and unhappy child much escapism and fantasist relief from familial unhappiness. In the last years of his life, this was to revisit him, but with a severe and last blow of disappointment; all which may have brought about his premature death from stomach ailments – which may have been stress-induced ulceration – incurable and giving him much pain.

Later, his ‘escape’ to Ceylon – a fantasist’s island par excellence – enabled his significant administrative achievements there. This very obvious success would have justified his escapism and fantasism to him; that is to say, as useful assets in his chosen day to day life.

Also, our Guilford and George IV loved dressing up (!) in, sometimes, bizarre and – in the case of the former – ancient Greek costume. And, as both grew older, their inclinations to do so became more emphasised and extreme. For Guilford, his own personal passage to the world of Ancient Greece – and transposing it into the then and now modern era – was the apogee of all his inner inclinations, which in his ordinary life and community became, and would have been seen as eccentric in the extreme.

But these eccentricities were found to serve the very highest of purposes and achievements, such as – the re-establishment of the Greek language as the first and foremost language of use throughout the new Greek State; the establishment of the Ionian Academy as the first Greek university of the modern era; the establishment of scholarships for very many promising Greek students, whom he was to identify as specially gifted – in which respect he was proved right in that many of these, his ‘scholars’, became either professors in his university or active in the public institutions of modern Greece; his own library collection of rare manuscripts and early books about Greece which, despite the provisions of his will, wherein it was stated that such were to be given to his university, were sold to the British Library.

But with this latter misstep and other twists of fate, this remarkable collection of books and manuscripts escaped destruction of the Corfiot ‘Guernica’ – that is, the German terrorist fire-bombing and brutal atrocity occupation of the island which took place on the 13th September 1943, after the Italian surrender to the Allies. The Germans, having destroyed many historical buildings, in its bombing of the Old Town of Corfu, finally occupied the island on the 27th of September 1943. Corfu was eventually liberated by British troops on the 14th of October 1944.

“The pen is mightier than the sword.”

[Edward Bulwer-Lytton from his historical play Cardinal Richelieu (1839)]

“Imagination is more important than knowledge, for imagination contains the whole world.”

[Albert Einstein’s quote in an interview with George Sylvester Viereck, “What Life Means to Einstein”, Evening Post (26 October 1929)] Corfu, 8 September 2023]

§

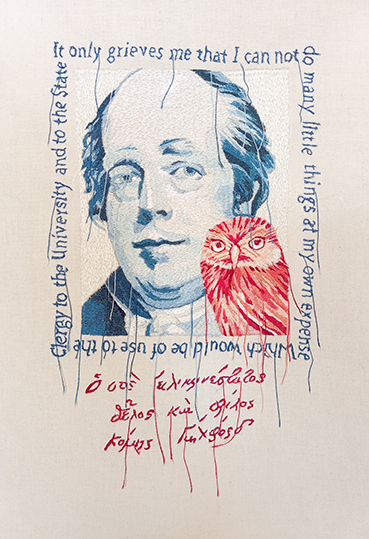

The need for one more special portrait of Guilford

By Megakles Rogakos, MA MA PhD

Philhellenism – the admiration of Hellenicity – is a unique phenomenon that focuses exclusively on the culture of Greece. There are Philhellenes all over the world. Their common denominator is the inheritance of the Grecian mind-set and culture according to the famous inclusive definition of Isocrates, “Greeks are those who partake in our education” (Isocrates, Panegyricus 4.50). Today it is institutionally represented by the heads of classical studies chairs in international universities and foreign archaeological schools in Athens – America, Australia, Austria, France, Canada, Denmark, Georgia, Germany, Holland, Ireland, Italy, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and Finland.

Guilford was and remains a leading Philhellene. Testimonies of his contemporaries present him as having an emphatic philhellenism, which prompted him to declare sometimes that he was Greek and not merely a philhellene and sometimes that he differed from his fellow countrymen that in England declared themselves as half Greek. So it was that he would sign as an “Athenian citizen” and would never remove the ring with the Athenian owl that was donated to him by the Philomuse Society of Athens (Nikolaos K. Kourkoumelis, Education in Corfu during the British Protectorate – 1816-1864, Athens 2002:155). In addition, his ancient togaesque university garb – despite the derisive comments caused by circles of the British civil service of the protectorate – gave prestige to the Ionian Academy and ushered it on the base of a unique university community in the European area. Thus it is that Guilford was and still is esteemed and praised by all cultured Greeks. His philhellenism was known throughout the 19th century, which was the era covered by portraits of him as were executed in his lifetime – that is, from 1790 to 1883. In fact, the endurance of his fame is such that portraits of him created after his death outnumber even those created during his lifetime. The portraits fall mainly into two categories – the first showing him in aristocratic attire and the second all’antico, in the manner of the ancients.

From the 20th century until today, however, the name Guilford – for the vast majority of residents mainly of Athens and Corfu – is nothing more than memorialisation merely by streets, as such carry his name in those two cities! Unfortunately, numerous other Philhellenes have suffered similar depreciation. For Guilford in particular, however, it is of huge importance to keep his memory alive – apart from anything else as an example to others – so that, somehow, and as adapted to the modern era, they may follow in his footsteps. Let it be known that thanks to him the modern Greek language is spoken.

The conquest of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottomans in the middle of the 15th century resulted in the sudden interruption of the intellectual life of Hellenism in general and especially of its educational life (Ioannis K. Vogiatzidis, “The gap in the spiritual tradition of the Greek people” in Historical Studies, Thessaloniki: Aristotle University 1933). The main reasons were the flight of almost all Greek scholars to Western Europe, the withering of the intellectual centres of the Byzantine Empire, the serious decrease in the population of the urban centres, the great decline of all economic activity and the impoverishment of the populations and the demographic changes that occurred in the conquered areas due to the flight of the local people and the settlement by Turkish or Slavic populations (Konstantinos K. Hatzopoulos, Greek Schools in the Period of Ottoman Rule 1453-1821, Thessaloniki: Vanias 1991). In the Ionian Islands during Venetian rule, the official language was no longer Greek, but Italian (in Venetian dialect). The local elite and townspeople preferred the language of the conquerors, with the result that Greek was self-taught only by the inhabitants of the countryside! The recognition of modern Greek as an official language in the Ionian Islands was established during the British Protectorate with the Constitution of 1817 (articles 4-6) and with the decisive contribution of Guilford. The use of the modern Greek language is due to him and he defended, more than the members of the Senate, its predominance in the Ionian Academy, which is the first Greek university of the modern era as founded by Guilford in Corfu, before Greece gained its independence. Guilford always considered the main goal of his Academy to be the progress and dissemination of the modern Greek language (Angelomatis-Tsougarakis, The Ionian Academy, Athens: Mikros Romios 1997:76). With his teaching staff benefited Greece, reforming its education in the best possible way!

The beginning of the unjust languishing of appreciation of Guilford’s hindsight can be traced to the unexpected fate of his statue created by Kosmas Apergis in 1883, which was sculpted to be placed alongside Adamantios Korais in the propylaea of the National University in Athens (Nikos-Dimitrios Mamalos, “The Adventures of the Statue of Guilford” in Portoni, Summer 2020, pp. 50-53). Although the sculptor had emerged as the winner of the competition, the Senate considered the final work unsuitable to be exhibited where it was intended to be. Instead it decided it would be better to set it up in Corfu. And there, however, a majority of the advisory committee (which included the artists Charalambos Pachis, Antonios Villas, Angelos Giallina and Vikentios Bokatsiampis), underestimating the artistic value of the work, decided to judge it as of average artistic value and agreed to its public installation only if the place found for it were “not very ostentatious”! Retrospectively, by today’s criteria, this particular negativism comes to the detriment not so much of art but of history more broadly. When cultural heritage is at stake, petty and envious differences should be put aside. Cultural universality should prevail.

It is surprising that on the 100th anniversary of the Ionian Academy, in 1924, no known celebration ever took place! Of course, all of Greece was recovering from the consequences of the ‘Asia Minor Catastrophe’ of 1922. However, on the occasion of the 200th anniversary, when the Ionian University makes leaps in extroversion and innovation, the creation of another portrait, even a non-material one, of Guilford should be seen as a critical and imperative need for Greece to honour its supreme admirer and cultural preserver and promoter.

§

Lord Guilford, an inspired supporter sponsoring education, reviving a legacy in knowledge and science

By Elli Droulia – Historian, ex Director of the Hellenic Parliament Library

True to the cause for the national regeneration of the Greek people and the establishment of a free modern state, Frederick North, 5th Earl of Guilford (1766-1827), today described in general biographies as “British politician and colonial administrator”, grasped the importance and the fundamental significance of the role of education for the Greek society. Education presented a definitive factor for the deliverance of the Ottoman yoke and the creation of a modern Greek state, established on the legacy of the ancient Greek heritage.

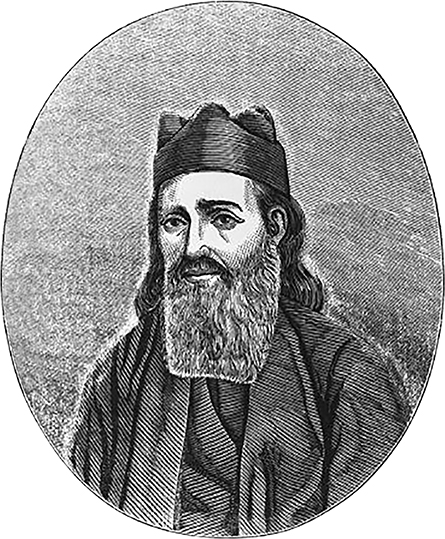

The Greek major representative of the Age of Enlightenment Adamantios Korais (1748-1833) argued that it was imperative to educate the Greeks as a necessary prerogative to arise successfully against the Ottoman Empire. His publishing programme stands as solid proof. Guilford sharing in principle the value of education and fostering a passion for ancient relics, inscriptions and manuscripts responded to the request for core education and protection of the treasures of classical antiquity, decisively and dynamically through a series of multifaceted actions. As early as 1813, before even the formation of the Filiki Etaireia (Society of Friends) in Odessa, notables of Athens and English consulate of the city founded the Filomousos Etaireia Athinon (Philomuse Society of Athens) out of philhellenic motives. Among the goals of the Filomousos was to “… see the sciences and to return to the Lyceum and the ancient Academy”, in other words to raise the intellect of Greeks through the establishment of schools, and the study, caretaking and protection of the ancient monuments. It remained active until 1825, when Reşid Mehmed Paşa otherwise known as Kütahı Paşa (1780-1839) besieged the Acropolis and finally occupied Athens in 1827. Guilford served as its president in 1814, as he was keen to support the above onjectives. Learning about the Filomousos based in Athens, Count Ioannis Capodistrias (1776-1831) then minister of Foreign Affairs of Russia, ardent supporter of the absolute necessity of mass education, undertook the initiative to persuade Tsar Alexander I of Russia to create a relevant Filomousos of Vienna. Kapodistrias throughout his life tried to develop favourable policies and inspired others to join the Greek cause and specifically to provide for the education of young Greeks, and later of the war orphans. Such is the case of Ioannis Chronis (1800-1879), who received a scholarship from the Filomousos of Vienna to continue his studies in architecture. The proposal to merge the two Societies to maximise results did not materialise, not even considered by the Filomousos of Athens.

In 1820, Guilford managed to become responsible for the overall education in the Ionian Islands while they were under British control, and the first Lord Commissioner of the United States of Ionian Islands was Thomas Maitland (1760-1824), who raised obstacles and difficulties in his original path. However, he obtained the position of “Lord of Education” and subsequently had the endorsement of the British government to shape the policies and administer the general educational system of the Ionian State, including the setting of a university, following European standards. Korais had stated that education ought to be structured in three levels of education (common, high schools, ‘modern’ high schools) and that western achievements should be contained to the advantage of the Greeks. Guilford created three cycles: a) Lower addressed to boys and girls in cities and large villages, b) Middle schools in the capital of each island plus one in Lixouri, Cephalonia, and c) Higher, at university level.

In 1824, Guilford materialised his vision to establish the Ionian Academy on the island of Corfu, the first university addressed to modern Greeks on soil inhabited by Greeks. He had invested in overall planning, coordinating, creating the appropriate political circumstances, allocating financial input, and most importantly, sponsoring, providing prospects to young, accomplished Greeks he recruited systematically personally.

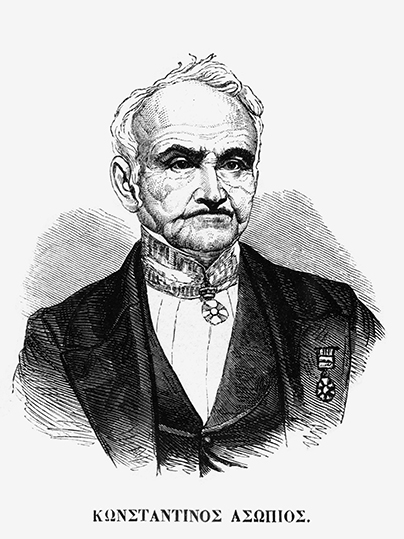

Moreover, in Zakynthos, Guilford had created an effective network of intellectuals, befriending, corresponding and exchanging views, cultivating ideas, offering his support or patronage. He, also, granted scholarships to several aspiring Greeks, as Konstantinos Asopios (1785-1872), Theoklitos Farmakidis (1784-1860), Christoforos Filitas (1787-1867), Michail Schinas, Spyridon Trikoupis (1788-1873) and later his younger siblings, Ioannis Karantinos (1784-1834) and others. Thus, they enjoyed the prospect of enhancing the standard Greek educational itinerary in Europe.

Instances and examples of Guilford’s benevolent and generous support were exhibited on various occasions. He financed the studies in mathematics of Ioannis Karantinos at universities in Italy and England, as well as at the French École Polytechnique in 1820. He stood by the side of Athanassios Politis (1790-1864) originally from the Ionian Island of Lefkada. Politis attended the School of the Aegean Island of Tenedos and continued to study medicine at the University of Pavia in Italy. While in Paris, he met Kapodistrias and he was introduced to Guilford. Guilford and Kapodistrias had met during the Vienna Convention in 1815. Both responded willingly to his request to supply the essential equipment to start a chemical laboratory in Corfu. Additionally, he chose to learn the Lancastrian teaching method, favoring mutual instruction among students themselves and the teacher, which he introduced as early as 1819 in Greek, and spread throughout all the Ionian public schools of the lower level, according to the general education organisation undertaken methodically by Guilford. He also taught chemistry for many years in a row at the Ionian Academy.

Below follow few cases of young Greeks who benefited by the offered opportunity for further learning and expertise. Guilford took under his protection and eased the way to further studies of young men who had already shown proof of their diligence.

Konstantinos Asopios (1785-1872) had met Guilford during the period he lived in Ioannina after his fathers’ passing. Being already an accomplished scholar, he pursued his studies with his financial support at the universities of Gӧttingen, Berlin and Paris. Guilford saw to the expenses of the studies at the German University of Gӧttingen in 1819 for Theoklitos Farmakidis as well. He counted on their teaching contribution at the Ionian Academy he was already planning to found. Asopios served as the orator and rector during the first year of the Academy in 1824. Indeed, they both taught for a number of years there.

Following Guilford’s death in 1827 and the subsequent waning of the institution, Asopios obtained a prominent position at the University of Athens. During three terms he served as rector (1843-1844, 1856-1857, 1861-1862), before retiring in 1866. On the other hand, Farmakidis had a turbulent career as a journalist, writer, politician, man of the church, professor at the Theology School of the University of Athens.

Guilford offered a scholarship under conditions, to the close friend and fellow villager of Asopios, Christoforos Filitas (1787-1867). Filitas had completed his studies in medicine, taught in the flourishing Greek community at Trieste, when he met Guilford. Filitas made a good impression on him, earned his trust and seeing his potential in letters, granted him a scholarship (1818) in order to learn the English language and study the Lancastrian method at the University of Oxford. In 1819, via Paris, Filitas arrived in England and settled in Oxford. In June 1820 moved to the Charterhouse in London to be initiated to the Lancastrian method. He stayed a few months, until September where he left Great Britain for Corfu. During his stay, he mostly catalogued and studied at libraries Greek manuscripts and early printed editions, rather than perfecting his English language skills and learning in depth the modern training method. Nevertheless, Filitas undertook the organization of the lesson of Greek language and literature in the Ionian schools, where the break of the Greek Revolution of 1821 found him. During 1842-1865, he taught at the Ionian Academy, Greek and Latin. He published among other, a Latin grammar.

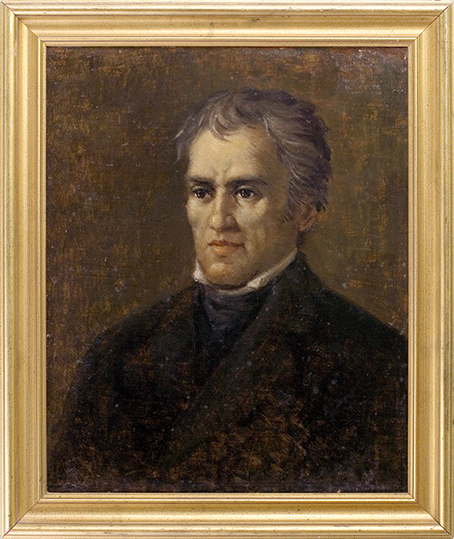

Spyridon Trikoupis (1788-1873) stands as a noticeable case and the most prominent example. Following his school years at his birth city and then at Patras, he was capable to pursue his studies in archaeology in Naples (1819) and letters in Paris (1820-1822), thanks to the support offered by Guilford. It is argued that they met either in 1810 or 1813 at the English Consulate in Patras, where young Trikoupis held a secretarial position. There, he had learned perfect English and good French. In the case of Trikoupis, “My dear Spiro” as Guilford tenderly addressed him during their life and regular communication, there was a closer relationship. He offered him the position of his personal secretary, to assist him with his Greek correspondence, and the Greek section of his library (1817-1822), while he could follow philological studies. He acted as a fund-raising agent for the 1821 Revolution working with Alexandros Mavrokordatos (1791-1865), his brother in law as he married his sister Aikaterini (1800-1871). He became not only a scholar, a writer, a public official engaged in politics but moreover a diplomat, being, among other appointments, the first ambassador of the newly found Greek state in England (1834-1838, 1841-1843, 1851-1861).

Guilford “picked” the young Greeks to be “his” proper fellows; in their later lives they excelled in their chosen fields and in life. They infiltrated the emerging Greek society with their new ways; they contributed by further imparting their knowledge as was his original will; knowledge and further training they had acquired during the course of their studies due to the Guilford’s offered care and opportunities. Jean Carandino (1784-1834) is considered the founder of modern Greek mathematics. Asopios has rightfully earned the title of “Rector of the Greek Letters”, leaving behind a legacy of important works and his mark until our days. Other eminent professors of the Ionian Academy transferred their teachings to the Ottonian University of Athens. Besides the academic career, fellows, teachers and professors followed multiple successful careers. Such an example is Konstantinos Typaldos-Iakovatos (1795-1867) who joined the ecclesiastical ranks and was a pioneer in reforming the Theological School of Chalke in Constantinople.

Acquainted with each other, they all shaped a strong bond, and in the later years, following the 1821 uprising, the crucial time of the state formatting era, the foundation age of modern Hellas, collaborated for a common educational benefit, and more.

§

I. PORTRAITS OF GUILFORD

1. Hugh-Douglas Hamilton (Ireland, 1740-1808). Portrait of Guilford, 1790, Rome.

2. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (France, 1780-1867). Portrait of Guilford, 1815, Rome.

3. Charles-Joseph Halmandel (England, 1789-1850). Portrait of Guilford after Ingres, 1815, Rome.

4. William-Thomas Fry (England, 1789-1843). Portrait of Guilford after John Jackson, August 1817.

5. Edward Orme (England, 1775-1848). Portrait of Guilford, 1 May 1818, London.

6. Ioannis Kalosgouros (Corfu, 1794-1878). Bust Portrait of Guilford after Pavlos Prosalentis, 1827.

7. Pietro Mancion (Italy, 1803-1888). Portrait of Guilford, c. 1830, Rome.

8. Petros Pavlidis-Minotos (Ioannina, 1800-1862). Portrait of Guilford, c. 1846, Athens.

9. Periklis Skiadopoulos (Greece, 1833-1875). Portrait of Guilford after Pavlidis-Minotos, 1873.

10. Spyridon Prosalendis (Corfu, 1830-1895). Portrait of Guilford after Skiadopoulos, 1882, Athens.

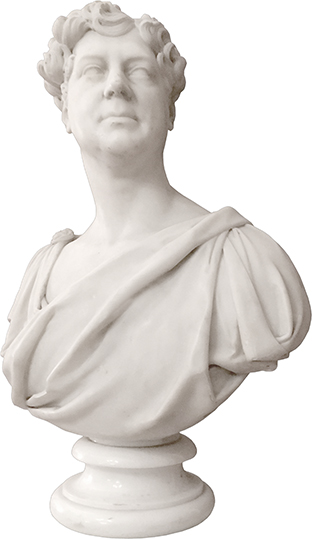

11. Kosmas Apergis (Tinos, 1836-1898). Statue of Guilford, 1883, Athens.

12. Anonymous (England). The late Earl of Guilford in his Greek College Dress, c. 1830, Corfu.

This picture of the young Guilford encapsulates the romantic vision of Rome. The sitter is positioned in the heart of the Roman Forum, centre of ancient Rome and home to the city’s most impressive temples and monuments. He stands, resting his hand on the wall before the Temple of Saturn (497 BC), with its familiar columns of the Ionic order, an icon of ancient Rome’s architectural heritage from Greece. In the distant background can be seen the Basilica of Maxentius (306-312 AD) and the Colosseum (72–80 AD). To Guilford’s right rests a broken fragment from the entablature of the nearby Temple of Vespasian (80s AD). Its sculpted representations include instruments of sacrifice: from the left to the right appears the horn of the bucranium hung with rope on the temple, the ceremonial jug containing the wine to be sprinkled on the head of the animal just prior to its sacrifice, the sacrificial knife for cutting it up and the patera (shallow plate) for holding the wine. Aged twenty-four, this is the earliest known representation of Guilford. His gaze seems to be lost in the reverie of the Classical world, of which he was so fond. He wears a blue tailcoat and holds, with his bare right hand, his hat and with his left hand his other, unworn, glove.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867) was a French Neoclassical painter. Although he considered himself to be a painter of history in the tradition of Nicolas Poussin and Jacques-Louis David, in whose studio he studied, it is his portraits, both painted and drawn, that are recognised as his greatest legacy. He was profoundly influenced by past artistic traditions and aspired to become the guardian of academic orthodoxy against the ascendant Romantic style, as exemplified by Eugène Delacroix and Théodore Géricault. Following the fall of Napoleon in 1815, Ingres found an enthusiastic clientele among the English tourists in Rome, who had flocked back to the city liberated from French rule. One tourist after another beat a path to his door wanting their portrait drawn. The first Englishman to sit to Ingres was Frederick North (1766-1827), 5th Earl of Guilford and youngest son of Lord North, prime minister to George III. He was an engaging eccentric, portrayed with a penetrating eye for his quickness of mind. Ingres made several drawings of Guilford, whose spare but lively descriptive pencil line impressed his sitter. One of these is in the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney. A passionate philhellene and linguist, North travelled widely and lived much of his life abroad. After a stint as governor-general of Ceylon (1798-1805), he led the campaign to establish the Ionian University at Corfu, becoming its first chancellor in 1824. When Guilford retired to London a few years later, he amused his friends by going about in academic robes, or turning up to dinner wearing the vestments of an archbishop of the Orthodox church, to which he was a convert. At the time of this work Ingres was unquestionably at the height of his powers as a graphic portraitist [Dr Mark Stocker, Curator, Historical International Art – April 2018].

Invented in Bavaria in 1796, lithography was still a new medium when Charles-Joseph Hullmandel (1789-1850), an English printmaker, enthusiastically took up the process in Munich and set up a printing press in London in 1818. This lithographic Portrait of Frederick North, Earl of Guilford is an early one in the history of the medium and was printed between 1818-1827, after the original drawing by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867). As lithography could produce numerous high-quality copies of an original, it was significant in the development of popularising obscure yet significant works, like this one, for a wide audience.